*Responses have been edited for length and clarity

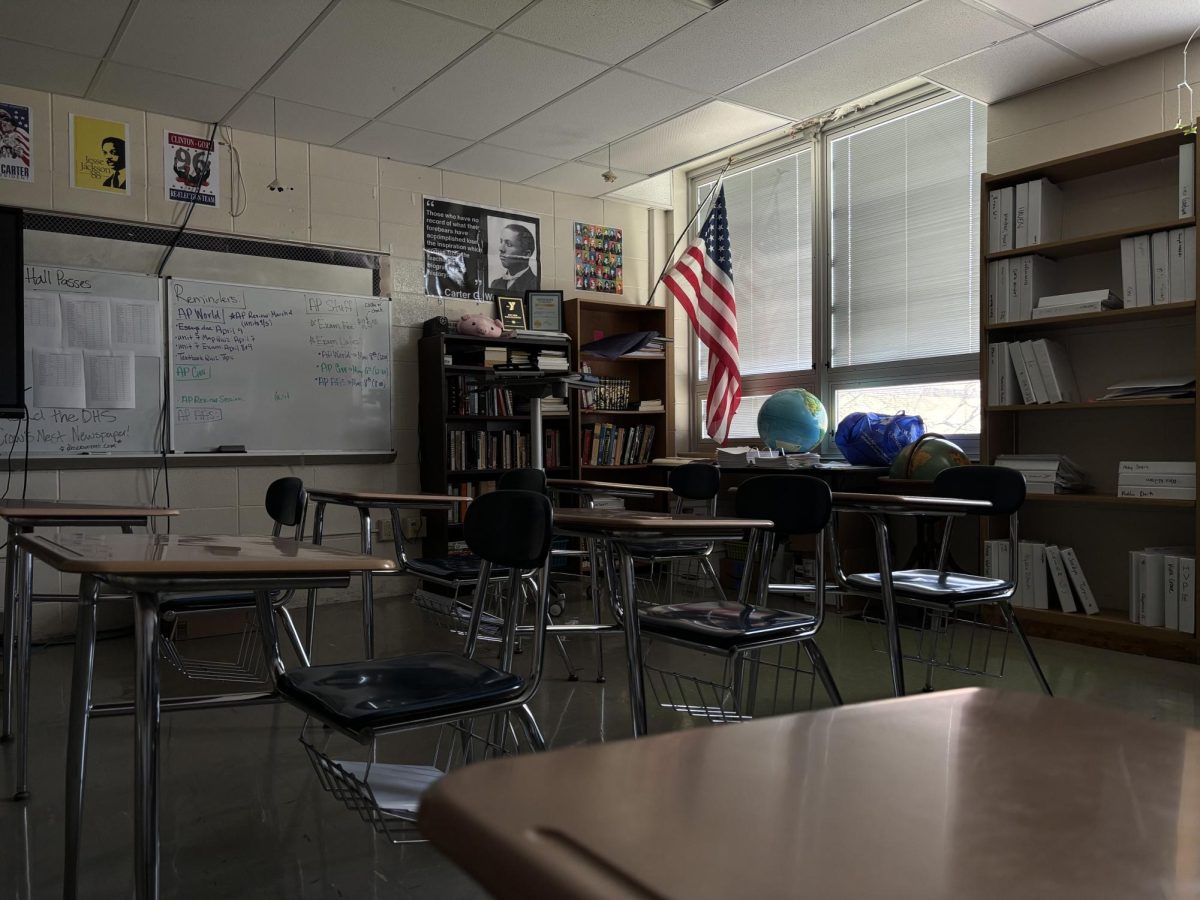

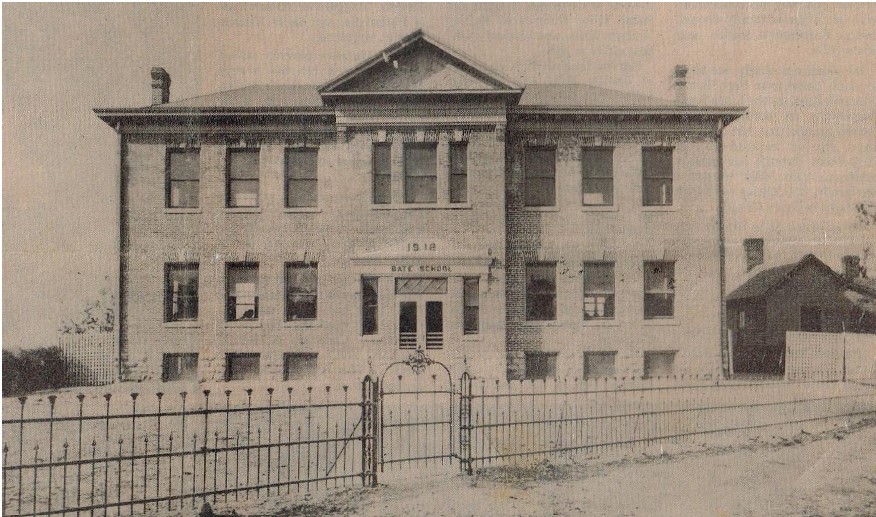

Michael Hughes is the President of the Danville-Boyle County African American Historical Society and graduated from Danville High School. For most of his childhood, Hughes attended Bate School until the Danville School System was integrated in 1965. Hughes sat down with The Crow’s Nest to discuss his experience of integration:

Q: The Danville School System was fully integrated by the 1965-66 school year. What grade were you in when you switched schools, and what was that transition like for you personally?

MH: I was a sophomore coming out of Bate, so I came into Danville High as a junior. Now, I probably had a different experience because I ended up doing fewer years at Danville since I dropped out of school in ’67. But anyways—the transition from Bate to Danville was — the word I want to use is “challenging.” Challenging for the Danville High students and challenging for the students coming from Bate.

Now, there were already students from Bate going to Danville High at the time, but the big push came in ’64 when Bate High School closed. Now, here’s one thing: for the students coming from Bate to Danville High, they were really — “apprehensive,” is that the word I want to use? — they really did not want to give up school. Bate School was a big tradition; it was a school that everybody loved. All of a sudden, you’ve been forced to give up that heritage and go to an environment where you were not really comfortable.

For the first few years at Danville High School, there were no Black cheerleaders; they were not offered the chance to participate. No Black homecoming queens, no candidates. It was a challenging time; it was learning to build an environment, because before Danville and Bate integrated, there was white Danville and there was Black Danville. The only interaction was during sports.

Now, one of the reasons I think integration was pushed in Danville was because of sports. For the ’63-’64 basketball seasons, Bate beat Danville both years. They didn’t want more than two Black people on the court — this wasn’t a Danville rule, more so an unspoken rule across high schools. That there were only to be two Black players on the floor at one time. And I think it was a challenge to the athletic department because they wanted to play the best and not adhere to the rule of “two Blacks on the floor at one time.” It was a very challenging time — it was far from the atmosphere that existed down in the Deep South, where it was very hard and there were threats of violence.

Q: I know you have talked about this a little bit, but can you describe the environment at Bate School? What was the sense of community like among students and teachers?

MH: It was community — that’s what was lost — a sense of community and a culture. You know, it’s hard to explain what that actually was; it’s hard to explain what a sense of community is. In Black neighborhoods at the time, it wasn’t uncommon for someone to live at one end of the street and someone else at the other, and all they would do was — there was no such thing as phone cameras or doorbells — they’d knock on the door, and the person inside didn’t go to the door to see “who is it.” They just said, “come on in.”

When that was taken away by urban renewal, it took away that culture. Bate was a fun place, but it was serious — they had talent shows; they had things like that. It was hard to give that up. The one thing that was missing at Danville that Bate had was that Black students didn’t feel closeness or connection to their teachers. A lot of the teachers at Bate knew your mothers and fathers, and they went to your churches. So the same kids they would see at church, they would also see at school. That was the closeness DHS didn’t have [for Black students].

Q: Can you describe your experience at Danville High School during the first year of integration? How did students, teachers, and the administration treat Black students who were transitioning from Bate?

MH: Yeah, it [discrimination] was there. It was disguised in a lot of ways, but it was there. White teachers were not comfortable teaching Black students at that time — not all of them, but some — because they were not used to it. One thing that was looked down upon in the community, especially at the beginning of integration, was interracial dating.

They couldn’t stop it, but at the same time, I remember a white girl and a Black guy — a friend of mine — started dating at Danville in the first three years [of integration], and they received so much pressure from the community, which transferred to the school looking down on it. They received so much pressure that the girl’s family moved out of town, and the guy dropped out of school. If you went to prom, you couldn’t go as an interracial couple; you wouldn’t be admitted.

Q: A document published by the Danville African American Historical Society includes an interview with former Bate teachers, Mrs. Gertrude Sledd and Mrs. Lucy Stephens. In it, Sledd remarked: “It hasn’t been too good for the South. Our children, they don’t aspire to lead. They don’t aspire to excel as they did at Bate School.” Do you think this was true in your experience? Did integration impact the academic aspirations or leadership opportunities for Black students?

MH: I don’t think it was to such an extreme degree. I don’t think there was ever a situation where all Black students were segregated into a room together. I don’t think Blacks got all the opportunities. I want to say there were no Black students on student council. I can’t quite remember when it was formed, but the Black Student Union was formed for that reason — because they felt opportunities for Black students weren’t being presented.

It was difficult, and I don’t know if the community was ready for that. It eventually got better. I am not sure if it will ever be 100%, but it’s a lot better nowadays than before. Back then, once Black students got out of school, they still didn’t get many job opportunities.

Q: Records from Board of Education meetings at the time of integration show that many capable staff from Bate School were not rehired at Danville High School. Did you notice this shift? What impact do you think it had on students and the school community?

MH: Five. Five male teachers, highly qualified, were not even given an interview at DHS. One of the teachers, Emmitt Bradus, was the coach of the 45th District Championship team that beat Danville in ’63 and ’64. How do you not get an interview for a coaching job? The reason they gave was because they didn’t want Black men teaching white girls.

Q: Were there any teachers or staff at Danville High School or Bate School who stood out to you as particularly supportive or unsupportive during the transition?

MH: The teacher that everybody — we have her name out on one of these benches — she was the most loved teacher. A Bate School teacher. She was a third-grade teacher, but if you ask any former students, I’m gonna say that 9/10 will say that everybody loved her: Mrs. Burton.

The support that was mentioned when we got to Danville High School — that was the kind of support Danville lacked. Some of the teachers had their picks. If they thought you were going to be successful or from a better family, they catered to you. She wasn’t like that. That’s what me and Linda, who you mentioned before, have talked about. Teachers had their picks.

Q: If you could speak to students today about your experience, what lessons would you want them to take away?

MH: If I could speak to students at Danville High, the main thing I want them to know is that their heritage comes from two places — from Bate, and from the African American community — and one of the things I think is important is that whatever the situation is, you can’t give up, you can’t just go.

Back then, a lot of students knew that once they got out of school, their chances of getting up in life—being President of the United States—were just about nonexistent.

Now, you have that opportunity.